Alva Myrdal, the woman who helped transform Sweden from a poor country into an example of development

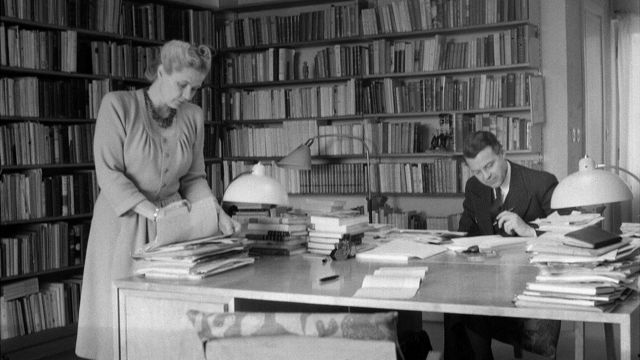

Alva Myrdal was one of the most influential social reformers of the 20th century; above, in photo by Jan de Meyere (1879-1950), number JdM 1802, Stockholmskällan

"We saw this competition, this race to build excessive and meaningless arsenals. My message here today is going to have to be that I believe the world is sick."

This is what the Swedish Alva Myrdal (1902-1986) said, with her typical frankness, in 1982, when she received the Nobel Peace Prize.

She had been born at the beginning of that century, in a very different world, where there were no nuclear weapons and Sweden, her native country, was almost unrecognizable: a land of farmers, poor and patriarchal.

"At the beginning of that century, Sweden was practically the poorest country in Europe, and Alva couldn't go to primary school because girls weren't allowed (to go to school) where she lived, in the countryside," says Kaj Foelster, one of their daughters to the BBC.

The young Alva devoured her library full of books by socialist authors and German and Swedish philosophers, which convinced her father "to support her so that she could study, but they had to pay for teachers outside of school".

In addition to what he learned in these private lessons, Alva gained knowledge about politics and ideas of social justice from his father, one of the first members of the Social Democratic Party that would come to dominate Swedish politics in the mid-20th century.

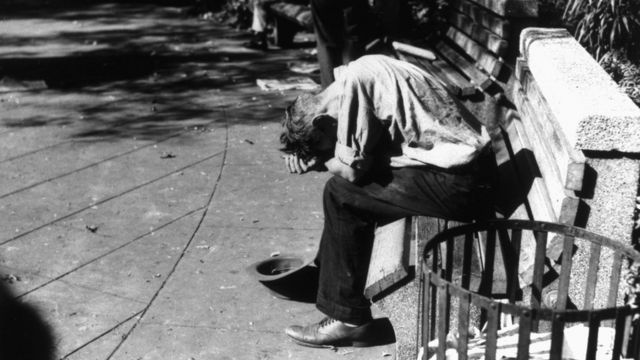

Sweden was once one of the poorest countries in Europe (Hornsgatan 1920-1930, Okänd fotograf, Standsmuseet i Stockholm)

Reimer was interested in new ideas, ideas that were soon taken up by his eldest daughter.

"Since she was three or four, she has sat under the table during meetings to listen to these men's debates," her daughter tells BBC Witness History.

bicycle love

At age 17, Alva met a student who changed his life.

While on vacation, Gunnar Myrdal went on a bike trail with friends, and one day he happened to stop at Alva's family farm.

"He thought he could brag about everything he knew, but when she asked him to read (German philosopher Arthur) Schopenhauer (1788-1860), he was surprised. That's how this great love began."

They were married in 1924, when Alva was 22, and they imagined it would be a union based on partnership, that they would live, study, write and adventure together.

The idea was that their union would be based on partnership, as it still seemed to be in this 1945 photo, in the couple's home office

Alva went to Stockholm to join Gunnar at the university. He studied law and later economics, an area in which he would win a Nobel Prize. She studied library science.

In 1929, when they were offered the opportunity to spend a year in the United States on a scholarship, they decided to accept — although they had to leave their son Jan, who was barely two, with his family in Sweden (something that, according to his other daughter, Sissela Bok, Alva would later consider one of the great mistakes of her life).

'This shouldn't happen with Sweden'

For both Alva and Gunnar, it was a turning point.

They arrived in the United States at the height of the Great Depression. And as they traveled across the country, what they saw surprised them.

"It was there and then that they became really politically aware. They were terrified that in the richest country in the world there was so much poverty, and they were convinced that this shouldn't happen with Sweden," says Foelster.

What they saw in the US in the midst of the Great Depression terrified them

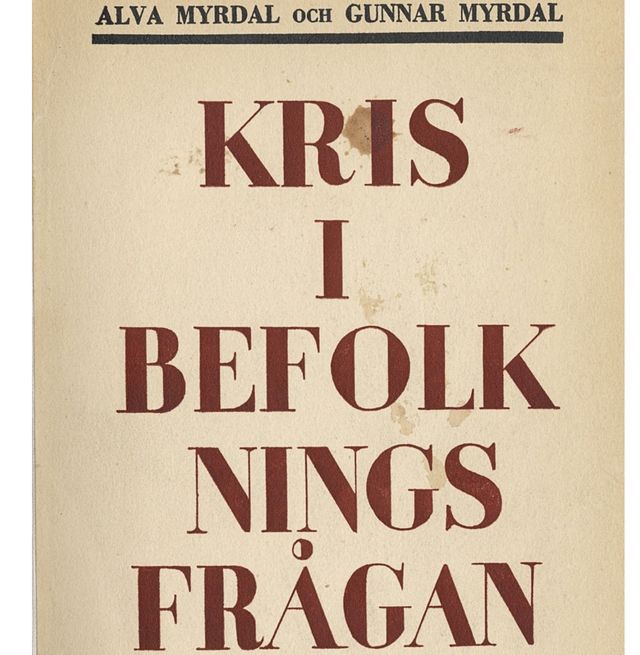

A few years after returning to Sweden, Gunnar and Alva published a book that caused an uproar in the country.

The work dealt with a hot topic: how to improve the country's birth rate, then the lowest in Europe.

In the work Crise na Questão da População , published in 1934, they argued that, in order to encourage people to have more children, state aid was needed.

There should be free medical care, contraceptives, and free school lunches; universal social benefits and better, more affordable housing.

Women should be free to work or study, creating places where their children can be taken care of during the day.

Alva and Gunnar argued that once all Swedes felt they had a decent basic standard of living, they would choose to have children.

And it worked.

"They came up with ideas that would allow all young families to get their place in society. That way they would want to have children. It was the most read book, and almost all of these reforms came true. It's called the Swedish Welfare State "explains Foelster.

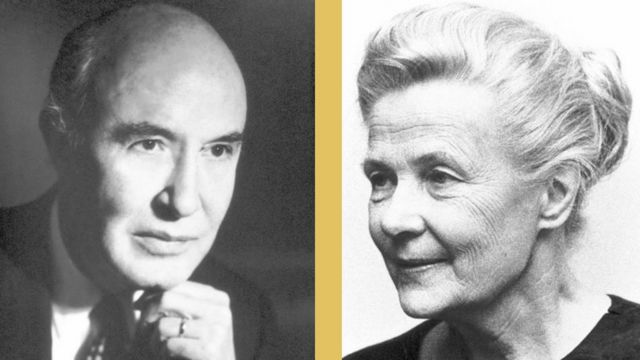

the illustrious couple

She and her sister grew up around the time their parents became famous, couple 20 who defied old ways.

They were attacked for their ideas, but they transformed Sweden

Foelster recalls that they "were attacked a lot... but my mother never got angry. It was a society steeped in political change."

"We had wonderful discussions. Gunnar looked at issues deeply, and Alva was always looking for solutions; he said there was always something that could be done."

Alva was described as the most modern woman of her time. Like many today, she juggled work, children, and a successful husband who wanted her help.

But in the 1930s and 1940s, there weren't many women working outside the home. How did she manage to manage this?

"Being very strict with time. From 6am sharp it was our 'family moment': for two hours we could have her just for us."

At 8 am, says the daughter, Gunnar's voice could be heard calling for her.

"She ran a kind of time-saver."

unequal relationship

Alva continued to campaign during these years: she founded the first school to train pre-school teachers in Sweden. And she saw how, one after another, the ideas she and Gunnar had articulated were adopted by the new Swedish welfare state.

But it was also clear that the partnership on which the union with her husband was supposed to be based was one-sided.

Book that caused transformation in Sweden was written with four hands

Gunnar was a brilliant economist, but he was also a petulant and demanding man. Everything was subordinate to his work, including his wife.

When the Carnegie Corporation chose him to conduct their monumental study of "The American Black Question," there was no doubt that his wife would leave the Social Pedagogy Seminary to look after him in the United States.

When, in 1945, it seemed likely that Gunnar would be appointed Swedish Minister of Commerce, Alva removed his name from the list of those considered for the post of Minister of Education in order to avoid a conflict.

When Julian Huxley asked Alva the following year to be director of the newly formed United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco), she refused because her husband did not want to move to Paris, the agency's headquarters.

However, he wanted to head the UN Economic Commission for Europe in Geneva and asked his wife to express her interest in his rejection letter. He got the job.

True to its principles, however, it was only after World War II that Alva felt able to leave him to make his way on the international stage.

Freedom

In 1949, she was the first woman to be invited to a senior position at the UN: head of the Department of Social Affairs in New York.

The following year, he went to Paris to head the Division of Social Sciences at Unesco.

She went out to walk her way around the world alone

In 1956, she published, in collaboration with Austrian sociologist Viola Klein, The Two Roles of Women , an influential work that was released before the advent of the second wave of feminism, but which anticipated many of her arguments.

And ended up prophesying also, inadvertently, a suffering that would lie ahead.

"Given that in the field of parenting there is the extraordinary situation of the product being in a position to judge both the producer and the production process, it is almost useless to aspire to perfection."

"Once they are old enough to read psychological literature, many children, however, will blame their parents for committing one sin or another or both."

But before those words reverberate in her own story, she still...

- Was chosen as sent from Sweden to India, where she remained until 1960;

- He wrote Our responsibility for the poor: a social first plan of development problems ;

- Was elected to Parliament as a Social Democrat;

- Planned and then chaired the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute;

- Became the only Minister of Disarmament in the world;

- Won the Nobel Peace Prize.

But above all, for two decades she devoted her passion and energy to one of the great themes of the Cold War: nuclear disarmament.

And in 1962, the Swedish government named her the country's top negotiator on the Eighteen Nations Committee on Disarmament.

army against madness

For her, the growing arms race was irrational and dangerous.

"She wasn't a radical pacifist," her daughter clarifies, "but she said she didn't understand how some people could be so crazy as to see the arms race as a solution."

For her, what the superpowers were doing was crazy

She insisted that disarmament would bring much greater security for both the superpowers and all the peoples of the world.

"She was very fond of the idea that there would be a whole army of opposition against this militarization," adds Foelster.

With a powerful women's movement backing her, Alva has assembled a coalition of unaligned voices to advocate concrete disarmament solutions, such as nuclear-weapon-free zones and a total nuclear test ban treaty overseen by seismic stations and satellites.

"She started out optimistic because she believed no one could be that crazy, but after ten years she wrote the book The Disarmament Game to tell the world what she had seen: that the two great powers had neither the desire nor the intention to stop." reminds Foelster.

"I can't give you good news about the disarmament negotiations. The truth is that what we've seen is a game, nothing more than a game," said Alva Myrdal disappointed.

Since there was no real disarmament after the signing of the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty in 1971, she considered her efforts a failure.

However, she had demonstrated women's leadership skills in a technically complex and crucial area of Cold War diplomacy, and her proposals later borne fruit.

But she didn't see

"In the other environments she had worked in she saw progress, but in this one, she didn't. And when she won the Nobel Peace Prize, she was very tired; she said it was a little too late," her daughter tells BBC journalist Louise Hidalgo .

1982 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Alva Myrdal and Alfonso García Robles of Mexico 'for their work towards disarmament and nuclear-weapon-free zones'

The award was given to her for her work in nuclear disarmament when she was 80 years old.

Days after the Norwegian Nobel Committee announced her choice, she had to endure the pain of seeing her son publicly turn against her and her husband.

Jan Myrdal, 55, author of works of fiction and political literature, has published a book whose title can be translated as Childhood , but also as The Child's Verdict .

And that was really what this was about.

The book spawned a series, was read on the radio on weekends, and several reviews were published in Swedish newspapers with headlines like "I hate my mom and dad because they never gave me love."

Alva Myrdal died four years later, in 1986.

In 1991, writer and philosopher Sissela Bok published Alva Myrdal: Memoirs of a Daughter , a clear response to the obscurity of the shadow her brother had cast over her mother.

No comments:

Post a Comment